DNSs are the system that computers and servers use to understand each other and correctly fulfil requests.

Oftentimes, many of the concepts that we run into over and over again in our intense day-to-day relationship with the Internet aren’t entirely clear. One of the terms that falls into this category is DNS. To start off with, DNS stands for Domain Name System, which actually clarifies things a bit, but then it starts getting a bit more complicated.

Back when the Internet was miniscule, domain names as such didn’t exist; you connected to websites using the IP address, a complex set of numbers. However, as soon as the Internet started to grow, it became hard to remember more than a handful of addresses, so computer scientists Paul Mockapetris and Jon Postel created the Domain Name System (DNS).

This system serves as the backbone of the inner workings of the Internet, connecting the domain names that you type into the browser with the IP addresses that are associated with them. To understand what DNSs are, and what role they play, we need to explain step by step the process that takes place when you visit a website.

How do DNSs work?

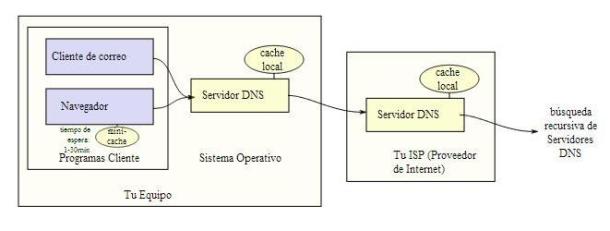

First of all, you need to know that every device connected to the Internet has an IP address. When a user is going to visit a website, the first thing that happens is that the phase 1 Client (which could be the browser or another application, in some cases) communicates with the machine’s local DNS server, which provides the DNS addresses that you enter when you configure the Internet connection. If the page is not saved in the machine’s local cache, it sends a request to the external DNS servers.

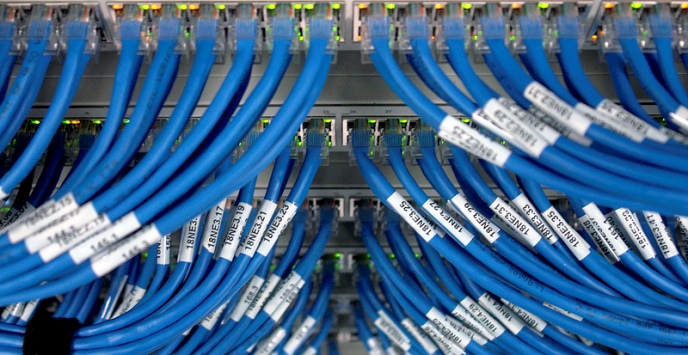

The DNS servers are the key to the whole process. Their role consists of translating the domain name into the corresponding IP address. To do this, they use a distributed hierarchical database that contains a series of domain names. This is where they go to verify whether the domain name is contained in the cache memory. If it’s not, they forward the request to another server.

This is where the concept of zones of authority comes in. Each one of these domain names has one (or more) domain extensions (like .com). These are groups of servers, generally with much greater capacity than the DNS servers, that have all the information on all of the domain names that are in their extension. When the request is received, they check which machine the domain is stored on and return the information. The DNS server on your machine goes to that machine and makes the request. It returns a specific address (a single machine can contain many websites), which your DNS finally puts in the browser to open the page.

Images: andrewfhart and Wikimedia