The story of Peter Higgs is replete with anecdotes: the rejection of his early work, deferred scientific encounters or his peculiar avoidance of the press are just some of the tales that surround the life of this great physicist.

The year was 1964 and a very young theoretical physicist by the name of Peter Higgs was frustrated to see Physics Letters magazine reject his second article on the formulation of the boson theory that would later come to be named after him.

The Briton received the letter of rejection with surprise because his first publication in the same magazine, in which he developed the mathematical formulation of his hypothesis, had not encountered any problems.

An editor working at CERN initially rejected his work

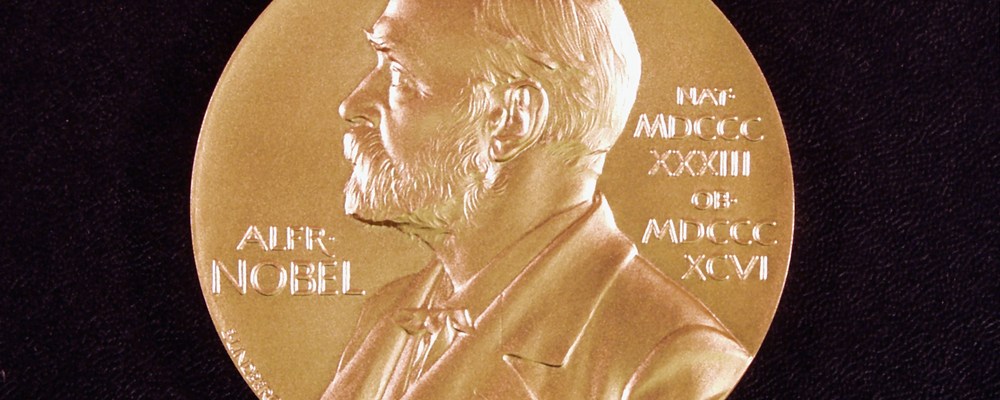

The story of Peter Higgs is curious, to say the least, and worthy of teaching in schools. Observing how his work was also rejected until he won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2013 shows how we must always press on when we stumble (personally or professionally).

Higgs’ first article actually explained in mathematical terms the errors in the assumptions made by another physicist named Walter Gilbert. If Gilbert’s proposals had been correct, perhaps the history of science would have gone in another direction and today we would be speaking of Gilbert’s boson instead of Higgs’.

But Gilbert was mistaken in his ideas, and Higgs could see the errors. But after the rejection of his second article, Higgs decided to continue his research, sending work to another journal (Physical Review Letters), which finally published his study a couple of months after publishing François Englert and Robert Brout’s theories.

The three scientists were responsible for the formulation of the boson theory of Brout, Higgs and Englert, currently known as the Higgs boson. The initial rejection of his work was taken by Higgs as «somewhat insulting», as he acknowledged in a recent interview.

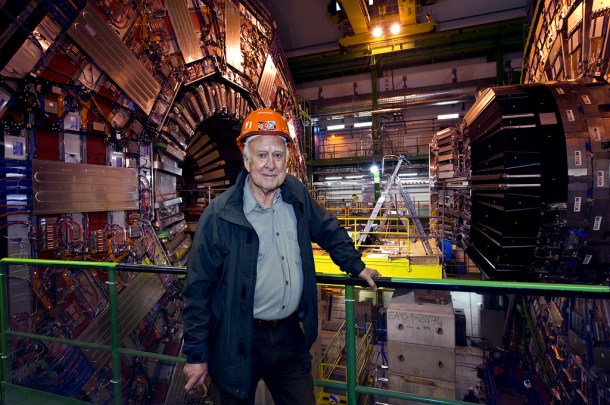

Paradoxically, the editor who told Peter Higgs that he was not accepting his work belonged to CERN, the institute responsible for confirming the existence of the so-called «God particle» a few months ago. The Swiss Laboratory’s work is undoubtedly the key to understanding the reason behind this year’s Nobel in Physics.

Indeed, it was in CERN that Higgs and Englert first met only a few months ago. Although their scientific careers had paralleled one another, it was at the press conference in which the existence of the famous boson was confirmed where the two scientists met face to face for the first time.

Higgs hid from the press just when the Nobel Prize was announced

But Higgs’ idiosyncrasies do not end there. During the official announcement of the Nobel Prize, there was a considerable delay at the start of the press conference. Why? Social networks made clear that the Stockholm jury’s deliberation was far from straightforward.

Furthermore, after it was confirmed that Peter Higgs, along with François Englert (as Robert Brout had died), would receive the Nobel Prize, the Swedish committee was unable to locate the physicist. It was later discovered on Twitter that after a bout with bronchitis, he had decided to take refuge from the press to avoid the onslaught of interviews moments before the Nobel announcement.

His example teaches us another important lesson: sometimes you need to know how to disconnect, even in the most «transcendent» moments of our lives. And how did Peter Higgs learn that he had won the Nobel? The answer was given by Ian Sample, science correspondent for The Guardian: A woman saw the British physicist walking in the streets of Edinburgh just after lunch. She got out of her car and hurriedly told him he had achieved the most important scientific award of his career.

Peter Higgs’ story is, without a doubt, full of curiosities and anecdotes. Almost 50 years after the formulation of his theory, his work has finally earned the recognition it deserves. And this year’s Nobel Prize recognises the immense progress made in theoretical physics by Higgs and Englert.

Images | Canada Science and Technology Museum (Flickr), Marc Buehler (Flickr), European Parliament (Flickr)