It’s Monday morning, the alarm bell rings at 8 a.m. and you wake up with a sore throat and a very stuffy nose. As you fix breakfast, you turn your computer on and open the application that links you to your emergency medical service. Your doctor performs a virtual examination and, after ascertaining that it is nothing more than a common cold, sends a prescription for medications to the online pharmacy’s application and puts your e-mail address in copy. Before nine, you pick up the items prescribed by your doctor on your way to work. At noon your doctor tweets you to see if you are better and at night, while you surf the net, you, along with many others, will have ‘liked’ the official Facebook site of the online healthcare application that is revolutionizing medicine.

Science fiction? As of a few years ago, an American remote healthcare project, Hello Health, runs out of Brooklyn (United States), as a free platform for doctors wishing to work virtually. It is supported by subscriptions from patients who, in addition to obtaining online healthcare, can access the results of any clinical analyses or their medical records online.

The Icor initiative, carried out thanks to the work of Telefónica and Parc Salut Mar of Barcelona, affirms that remote monitoring can reduce deaths due to cardiac insufficiency by 34%. Similarly, in the UK the creation of a platform foronline monitoring of chronic patients suffering from hypertension has helped optimize healthcare services, saving 10 million pounds in 5 years.

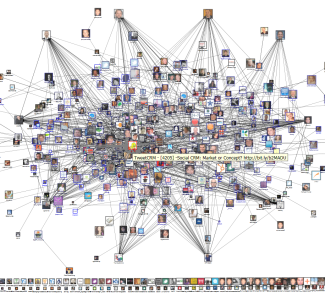

It is increasingly common for patients and healthcare professionals to search for information on the Internet. According to the United States’ CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), in 2014 69.3% of US Internet users used social networks at least once a month. We are thus heading towards a society in which healthcare users increasingly search for information on the net. In addition, smartphones are becoming an indispensable tool: over 85% of adults in the United States have a mobile telephone. Information and the tools to find it are available. But how to the different users of the healthcare system respond to the new 2.0 world?

On one hand, despite the above examples, digital interaction between healthcare professionals and patients is not yet a consolidated reality; however, it seems likely to occur in a near future. As explained by José Antonio Plaza in Diario Médico, “progress has been made, as we were starting from scratch, but the trinity of doctors-patients-web 2.0 is still in its infancy, although we are approaching a reality of informed users”. The risk of misinformation on the Internet must surely be mitigated by creating a community of users who are more involved in their healthcare and in monitoring their treatments.

Several healthcare applications have been developed for this purpose, with the aid of social networks, mainly intended for 2.0 patients. This progress falls within m-health, a branch of e-health based on the use of mobile devices. GoMeals, for example, the Sanofi app for diabetic patients, allows their diets and nutrition to be monitored. There are also mixed applications, intended for both healthcare specialists and relatives and caregivers of patients with Parkinson’s disease, such as Neurolinks, with the endorsement of the Spanish Neurology Association.

A the same time, the presence of healthcare centres on social networks is increasingly visible: according to Mashable, 26% of hospitals in the United States already use different channels such as Facebook and Twitter. In Spain, although the use of social networks is not as widespread, there are examples such as Sant Joan de Déu Hospital in Barcelona, which is present on the main networks, providing more direct and accessible information to patients.

At the same time, healthcare professionals, far from being left out of the net, are creating an increasingly strong community with a growing Internet presence. This is where they can search for information, connect professionally with their colleagues (particularly via LinkedIn or Xing) or even present clinical cases with educational or research aims, as Dr. Rosa Taberner does in her blog Dermapixel.

The advent of the doctor 2.0 and patient 2.0 does not seem to be very far off. In light of this, specific social networks have been launched oriented to both communities, to meet their needs and demands. Some examples include the Esanum and Sermo platforms for health professionals, as well as the innovative concept of the Fórum Clínic, an interactive program so that patients can experience greater autonomy in their healthcare process. Another Spanish project, Somos Pacientes, brings the main Patient Associations of the entire country together, which guarantees a greater capability for contact between users and improved access to specialized training and the latest scientific discoveries on their diseases.

As Peter Drucker used to say: “the best way to predict the future is to create it”. It may be that one of the weekly conversations on Twitter on health and social networks (in Spanish, in #hcsmeues) will lead the way to the hitting the right key so that communication 2.0 between doctors and patients creates the perfect melody, and sooner than we imagine.

Image | European Commission