There is no doubt that the search for the materials of the future is at nanoscale levels and that, in this race to discover supermaterials, graphene is the undisputed star for its excellent properties, despite the difficulties in mass producing it at a competitive market price. But this long-distance race between laboratories and research centres to discover and develop new nanomaterials capable of matching or exceeding the properties of graphene, has already been joined by some competitors such as molybdenite or even newer ones like nanocrystalline cellulose. The latter, nanocrystalline cellulose, has aroused the interest of the scientific community because of its possibilities for mass production at low cost, far exceeding the expectations for graphene production and development. But before we delve into the subject, we should ask:

What is nanocrystalline cellulose?

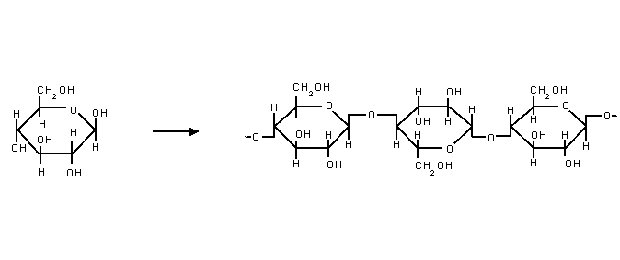

First, we note that it is a nanocomposite of vegetable origin, obtained either by compressing fibres or by natural cultivation through the independent production of different types of bacteria. This material is nothing more than a nanometer scale biopolymer composed exclusively of β-glucose molecules, but the most interesting thing is that this organic biomolecule is found in large quantities as part of the Earth’s biomass.

The most salient factor of this finding is that, as with graphene, the development of nanotechnology allows new properties hitherto unknown in many materials to be studied and discovered. In this regard, among the novel properties of this new material would be its capacity to multiply the strength of steel by up to eight times, its extremely light weight and excellent electrical conductivity.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=R3HH4iN8aDM[/youtube]

To what extent would nanocellulose improve the performance of graphene?

In principle, nobody has been able to demonstrate this until now because the material’s technology is in an initial phase. Among its future fields of application are the biofuel sector and the pharmaceutical industry, but also others such as electronics, where graphene is currently the reference product. According to Amador Fernández Velázquez, researcher and contributor to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology through the ITMA in Asturias: «It is a good nanomaterial and has electronic properties. But I don’t think it will be in direct competition with graphene. Graphene will continue to hold its own because, for example, no other material can be isolated into a single layer».

One of the great challenges of nanocellulose is large-scale production, because, as with graphene, its limited production could make it unfeasible for use in certain technological applications. However, cellulose is found in large quantities in nature and, therefore, the challenge faced by researchers resides in synthesizing cellulose to obtain nanocellulose on a large scale.

Until now, the production of nanocellulose has not been profitable because it required a significant economic investment, either in the fibre compression process or in order to supply nutrients to the bacteria that naturally produces this material. Now, scientists at the University of Texas, under the guidance of Malcolm Brown as director and member of the research team, have managed to produce small quantities of nanocellulose from a certain type of algae capable of producing the material naturally, without the need for nutrients. Brown says that despite having achieved only small amounts of nanocellulose, they are genetically modifying the original algae, introducing genes from the bacterium Acetobacter xylinum, used to make vinegar, which help produce massive amounts of this nanomaterial. On the other hand, production costs would be minimal since production only requires water, sunlight, and this type of algae to produce the nanocellulose naturally.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=FksunaSFABk[/youtube]

Future applications of nanocrystalline cellulose

As researchers note, the strength properties, the extreme lightness and excellent electrical conductivity of nanocellulose make it an ideal material for making protective vests, ultralight electronic device screens and even to grow human organs. But it should be remembered that the development of this material is still in its infancy and although the properties of the crystalline nanocellulose point to certain technological fields, it is possible that future research will broaden the range of applications to other, hitherto unimaginable, sectors. In this regard Amador Fernández reminds us that «in the beginning, everyone was focused on the strength properties of graphene, but then its great field of application has been in electronics.»

Financial details of the business of crystalline nanocellulose

According to Malcolm Brown, this research could be «one of the most important discoveries of botany» and estimated that this natural production system would be in full operation within approximately 5-10 years.

As Brown points out, mass nanoscale production of this cellulose requires minimum production costs because it is abundantly found in nature. Moreover, from the environmental point of view, it would not be necessary to use whole trees for its production; that is, branches, cuttings from the timber industry and even sawdust could be used, says scientist Jeff Youngblood from the Forestry Institute for Nanotechnology of the University of Purdue. In fact, the Ministry of Agriculture of the United States last year invested $1.7 million in the creation of a wood treatment plant for production of crystalline nanocellulose, through the Forestry Products Laboratory. According to the U.S. government itself, it is estimated that the industry will move the succulent figure of over 600 billion dollars in 2020. The challenge now is to show that it is possible to produce it in large quantities, as stated by Malcolm Brown, and demonstrate with economic performance figures that this prodigious material is actually cheaper.

Images | via NewScientist